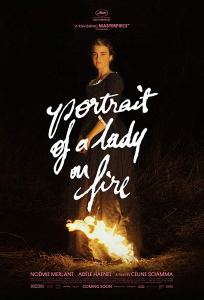

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

Premise: On an isolated island in Brittany at the end of the eighteenth century, a female painter is obliged to paint a wedding portrait of a young woman.

Maybe it’s reductive – cliché, even – to say that there’s nothing quite like your first love. Maybe, for some, it’s not your first that you remember most, but someone who opens your eyes and shows what true human connection can be. These are only some of the themes explored in Céline Sciamma’s latest film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Heartbreaking but hopeful, complex but familiar, Portrait tells the story of a doomed romance between two young women in the 18th century – one a painter (Noémie Merlant) and the other her muse (Adéle Haenel), the daughter of a wealthy family who is betrothed to a man she’s never met.

But this is more than just another film of a forbidden love, summer romance, or even of star-crossed lovers. Sciamma’s script has much more to say about permanence and memory, how even the briefest relationships can make a lasting impact, and how we choose to reveal ourselves, in spite of the fear of vulnerability. When Marianne (Merlant) arrives at the home of Héloise (Haenel), she is commissioned to paint a portrait of a subject who refuses to be painted. A previous artist had tried, but was fired before he could finish, leaving a faceless representation (a funny and clever metaphor that thankfully isn’t underlined too heavily). In order to find enough reference material to use, Marianne must follow her, studying her features closely without giving herself away. It’s here that the two begin to bond, and slowly realize there is something they share that they’ve never been able to express to anyone before. “Being free is being alone?” Héloise asks near the beginning of their encounters, and her simple line carries with it the weight of a lifetime of oppression and misunderstanding.

Shot primarily in two locations – the home, and the nearby beaches of Brittany where Héloise often walks – Portrait of a Lady on Fire looks gorgeous without coming off as too showy. The blues of the sea with the yellow ochres of the sand pair beautifully with the distinctive green and red dresses of the two women. Interiors (mostly in the painting room) are strikingly, naturally lit; in here they can see each other for who they really are.

Despite its period setting, Portrait of a Lady on Fire feels hauntingly modern. Sciamma, however, doesn’t fall back on conventions to make a contrived statement on modern gender roles or the persecution of sexuality. Instead, she inserts a recurring theme of mirrors throughout this film. Or, rather, how we see ourselves in others. There’s even a humorous visual moment involving the placement of a mirror when Héloise asks Marianne to draw herself.

Watching this film, it’s hard not to see the comparisons to 2017’s Call Me By Your Name. Both concern closeted homosexual romances in period settings, though this one is noticeably devoid of any peaches. And whereas Call Me By Your Name’s conflict – or lack thereof, in this reviewer’s opinion – centered on self-discovery, this film’s priorities lie more with the importance of self-acceptance. They even share a similar final shot, where Haenel truly gives Timothée Chalamet a run for his money. Call Me By Your Name, while still telling a unique story, lacked the stakes that this film does to fully sell itself as a doomed romance. We know that Elio and Oliver will remember each other after they leave one another, but we never see how their longing manifests itself (yes, there has been a sequel book written, but for these purposes, we’ll ignore it). Here, the payoff is beautiful. I don’t know if I’ll be able to look at the number 28 without thinking of this film in the future.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire surely won’t go down easily with mainstream audiences; there’s hardly any music, it’s all spoken in French, many of the scenes are quietly soothing and monotone in volume, it’s a period piece, and none of the actors are well-known in America. But Sciamma deftly strips it of any arthouse pretension that could make it wholly inaccessible. It’s common for a film critic to slap the “masterpiece” label on a great film, and you’ll surely see a lot of that with this one, especially as a way to lure skeptical audiences in at a time when non-Disney affiliated intellectual property is far from a safe bet. In the grander scheme of things, I’m admittedly still a bit of a film neophyte, so I don’t feel confident enough to say the “M-word” here, but Portrait of a Lady on Fire is emphatically a must-see, a perfect way to end a decade of film.

About the Writer: Ben Sears is a lifetime Indianapolis resident, husband, and father of two boys, as well as a contributing writer on ObsessiveViewer.com. Aside from watching movies and television, Ben enjoys photography (bensearsphotography.com) and running marathons, but never at the same time. That would be difficult.

Help me in the fight against homelessness in Indianapolis by donating to the Wheeler Mission via my fundraising page for the 2020 Drumstick Dash.

Find more of Ben’s columns here.

Follow Ben on Letterboxd